(Part 3 of 3) "Digestive Dysfunction Deep Dive" Video Series: The 7 Consequences of Low Stomach Acid

(Transcribed below)

Here we are in part 3 with a bit of a doozy. This video will do a lot of heavy lifting for us in terms of explaining the most common types of digestive dysfunction.

As always, feel free to rewatch as many times as you need to.

In the previous video we talked about some of the indirectly associated forms of digestive dysfunction to stomach acid. Now, we'll get into the many forms of digestive dysfunction caused directly by improper stomach acid levels.

So before we go any further, it's useful to define how we measure acidity, so that you understand what I'm talking about when I talk about stomach acid levels.

Acidity is measured using a system called pH or power of hydrogen.

This scale runs from 0 to 14 where 0 is the most acidic, and 14 is the most basic. and 7, in the middle is neutral. Water, for example has a pH of 7.

Literature has shown that a pH level between 1.5 -3.0 in the stomach is fundamental for proper function - this is very acidic, along the lines of battery acid.

Likewise, when it's outside of this window, health consequences begin to ensue.

So in this video we're going to look at 7 major consequences for what happens when stomach acid levels are too weak or when the pH is too high.

Got it?

Onward!

So let's pick up where we left off and return to the esophagus.

Consequence #1: LES signalling dysfunction leads to acid reflux, heart burn, and GERD.

The first consequence of low stomach acid happens when the LES (gateway) dysfunctions by opening and closing at the wrong time.

This, in turn, leads to acid from the stomach spilling up into the esophageal tissue and burning it, resulting in conditions such as acid reflux, heart burn, and gastro-esophageal reflux disorder (or GERD).

Let's look at this closer.

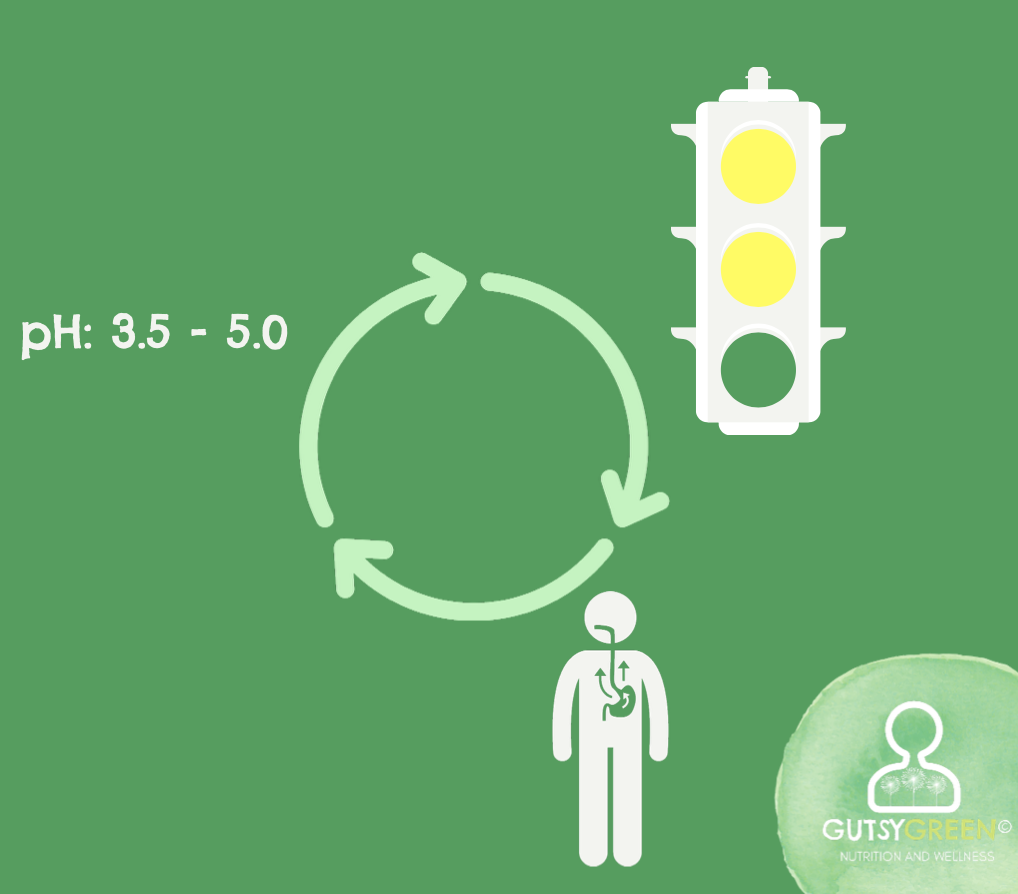

One of the reasons the pH of the stomach is so important is because the low pH serves as a signaling mechanism for OTHER bodily functions to begin or end - kind of like a traffic light. You can imagine that if a traffic light isn't working correctly, quite a bit of damage might happen.

Usually, the stomach's potent pH would work as a warning to the LES by saying "I'm burning in here, stay shut - red light! red light!"

However, when the pH is too high, the LES gets the wrong signal - a yellow light maybe, or in terrible cases a green light. So it remains open.

You may wonder, “So what? The stomach acid isn't that acidic anyway since it's not below a pH of 3.”

Wrong.

It's still plenty acidic enough to do damage to the tissue, if it's hovering at a pH of 3.5-5.0, but it's not acidic enough to properly calibrate the mechanical function of the LES gateway.

It's a classic case of too hot yet not enough.

It may be counter intuitive but restoring acid levels back to proper pH kicks this signaling back into gear, and allows the LES to start closing when it's supposed to.

The answer is more acid for these populations.

The inevitable question here is, wait a second, then why do antacids work if the problem is actually that I need more acid? This is a great question and the answer can be a bit shocking, so brace yourself.

Antacids and acid-blocking medication work by neutralizing your stomach acid and bringing the pH to between 5.0 and 7.0. Do you remember what else has a pH of 7.0?

Yes, water. This way, when your LES stays open, whatever bubbles up from your stomach won't burn your tissue, because it's been neutralized and basically turned into water.

Sounds like the perfect solution... if we didn't require stomach acid to protect us, digest food, and receive nutrients. But, can water break down our food?

Let's think of an experiment, where we put a meal's worth of food in a big bowl of water and let it sit out for a few hours. When we come back to check on it - is it broken down? Are there bacteria growing in it? Mold? Rancid fats and putrid proteins?

I think you can see why this may be a problem. We don't want this scenario happening inside of our bodies - we want our food to get broken down before it rots! So the antacid "solution" does provide symptomatic relief - but at the cost of lowering your acid barrier and depriving the body of nutrients.

My friends, there's a better way.

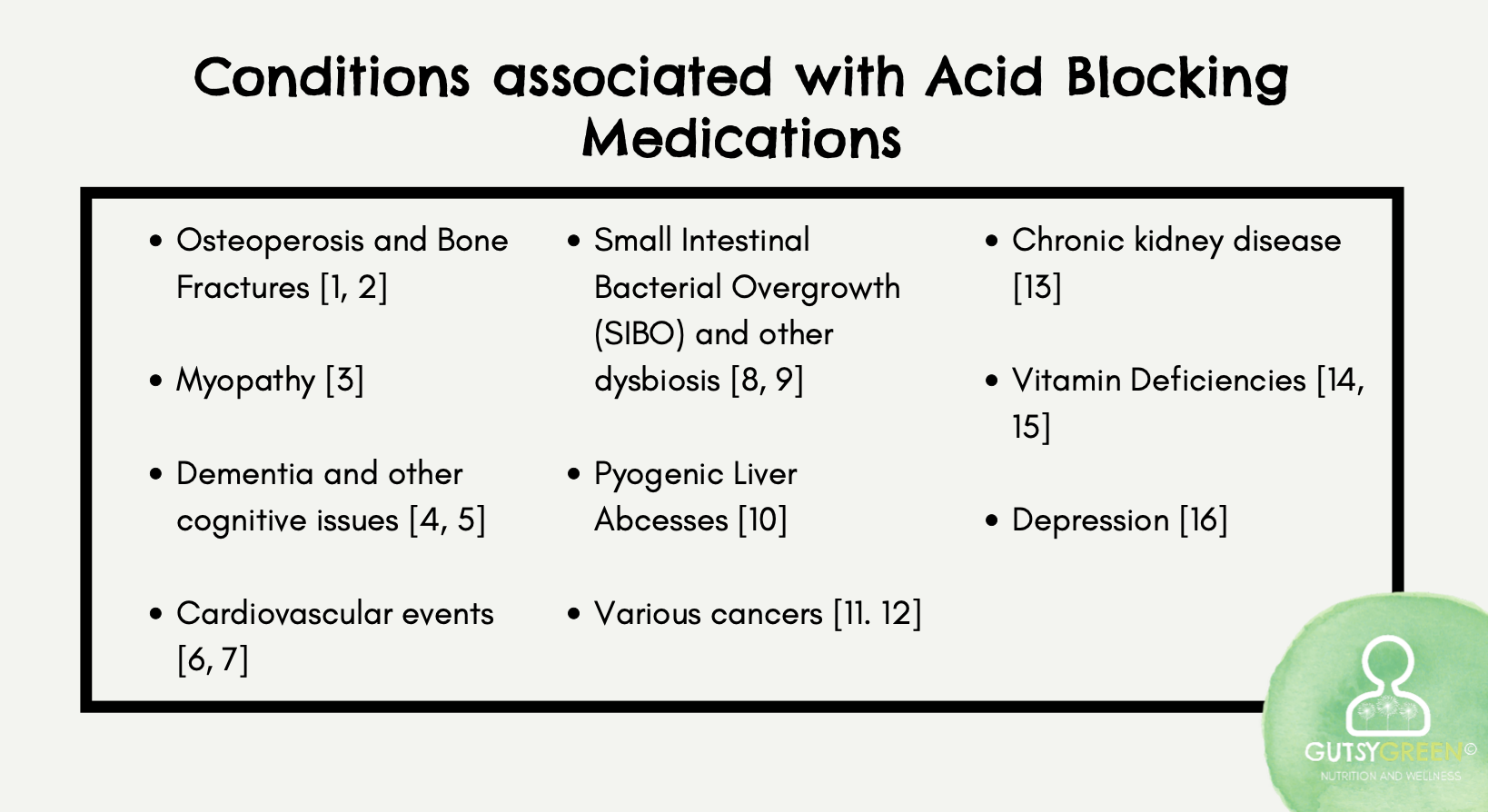

So just to kind of shine the light on this, there's actually a considerable amount of emerging data highlighting the disturbing relationship between acid-blocking medications and disease.

So we can see that its long-term use significantly increases the risk for bone conditions, myopathy, dementia and cognitive impairment, cardiovascular events, intestinal dysbiosis, liver abscesses, cancers, kidney disease, nutrient deficiencies, and depression. Just to name a few.

In fact, it says right on the packaging for Prilosec that it isn't recommended for long-term use. Why this isn't made common knowledge and the conventional medical community continues to overprescribe these substances is unclear. But as of now, over 15 Million Americans are on PPIs via prescription, and many more use over the counter versions.

To be absolutely clear: Your use of PPIs or acid blocking medication should be discussed between you and your doctor. This is not medical advice, only education. Please involve your doctor in any decision you make going forward.

OK, moving on. Now that we've explained the dysfunction in the esophagus, we're moving on to the main player in this game: the stomach.

So we briefly talked about the role of stomach acid as a barrier component of the immune system in the gut primer e-course, but we'll delve in a little deeper now with consequence number 2.

And if you haven't watched this series yet, I suggest going to watch it now, and then returning to this video when you've completed it.

Consequence #2: The acid barrier, our first line of defense, becomes compromised.

The Acid Barrier can be considered our first line of defense for microbes and antigens that enter our body through the mouth.

To rehash: the acid reduces them like any other food particle to their primary chemical components of glucose, amino acids, and fatty acids, and then we digest them accordingly.

Likewise, when this barrier is compromised, say, if the pH is similar to water in the stomach, or even if the pH is just a little too high, microbes stand a much better chance of surviving in the stomach or intestines, finding a hospitable home, full of incoming nutrients, where they can colonize and proliferate and wreak havoc!

So we can help to ensure that we have a shield against these critters in place when we optimize our stomach acid levels.

This gives way to an interesting discussion about what causes disease and illness. There's this sort of chicken or the egg question about whether the microbial presence causes illness, or whether it's actually the terrain in the body.

I subscribe to the theory that it's actually both.

Obviously, if there is no microbe present to infect you then of course you will not fall ill. Thank you Louis Pasteur for putting this reasoning forward! This is really the side of things that modern medicine emphasizes with a heavy hand, employing methods such as sanitization, antibiotics, and sterilization.

However, equally important, according to dear Antoine Bechamp, is the internal terrain. In other words, if you have an optimal environment, in this case a sufficient acid barrier, your environment is inhospitable to intruders, so they won't be able to survive, colonize, and make you ill. This could also be applied to the intestines - if you have plenty of beneficial microbes present it's much harder for pathogenic ones to colonize.

So in thinking about this, one of the best preventatives for infections and illnesses of all kinds is to optimize the acid barrier.

Populations who especially need to think about this include those experiencing repeated infections of any kind - sinuses or kidney. If you get a lot of traveller's diarrhea or traveler's constipation, if you feel like you get sick all the time, if you have dysbiosis that doesn't seem to respond to intestinal protocols, or if you've had more than a few bouts of food poisoning in your life.

The good news is that we have a great leverage point to start optimizing your your terrain by fixing your stomach acid.

Alright so on to consequence #3: if the pH of your stomach is too high, then it follows that the food in your stomach will fail to break down properly.

Consequence #3: Release into the Small Intestine is delayed, and food rots.

This lack of break down contributes to delays in movement through the GI. Which leads to a few outcomes.

Just like in esophageal dysfunction, this delay in emptying time has to do with a misfire in the signaling pathway which depends on stomach pH falling between 1.5 and 3.0.

When pH rises above this point, it delays when the stomach empties its contents into the small intestine.

Usually the conditions that need to be met in order for this emptying to happen normally are a low pH as well as the food being in a liquified form absent of large undigested particles. This is the "safe" part of the safe sludge.

When these particles are still present in the stomach mixture, likely because of a high pH - it leads to a signaling delay.

The pyloric sphincter defaults to not opening so that the stomach can continue to hold and break down the mixture further - ensuring its suitability for the later steps.

This may as much as double the time the food spends in the stomach.

And while the stomach's structure is designed to be able to withstand an acidic environment for 2-4 hours while food breaks down, it is not designed to withstand continuous windows of time exposed to these potent acids.

This slow emptying, in turn, elongates the time that the stomach lining comes into contact with the acidic mixture, and the extended contact can result in damage to the mucosa and inflammation of the stomach lining.

This is why a feeling of an acidic stomach is a strong indicator that, actually, more acid is needed in order to speed up the rate at which food moves through the digestive system.

A delay can also result in the food having more time to ferment and putrefy since it's moving so slowly through the GI tract without being properly neutralized.

This makes it much more prone to things like oxygenation, and the production of dangerous byproducts that speed-up aging such as Advanced Glycation End-Products.

So in order to make sure our food is friendly and not a steaming cess-pool of toxic sludge, we need to resurrect our stomach acid.

Consequence #4: The pH fails to signal the release of the pancreatic juices, resulting in burns and undigested food.

Consequence #4 of low stomach acid happens when the food finally does get released into the upper part of the small intestine, and it is acidic but not acidic enough to trigger the juices from the Pancreas to be released. One of these juices is Bicarbonate which works to alkalinize the chyme to a neutral ph.

This neutralization allows the food to safely reside in the intestine's sensitive and fragile tissue without burning it.

But, Because the pH of the food isn't strong enough to trigger the pancreas juices, the neutralization doesn't happen, which can result in intestinal burning and ulcers.

What's more, the pancreatic enzymes, which depend on the neutral pH, do not get released either, and so food remains much more intact where it would have been broken down in a properly functioning system with normal stomach acid signaling cascades.

This lack of signaling in the pancreatic pathway, leads to a lack of signaling that disrupts the liver gallbladder pathway and leads to consequence #5.

Consequence #5: The pH fails to signal the release of bile from the liver and gallbladder leading to fat maldigestion.

Usually the liver and gallbladder work together when they detect chyme with a neutralized pH (from the pancreas) to then release thin and potent bile. This bile emulsifies fat particles and is a necessary step for the fat being usable to the body.

If stomach acid is low, and the pancreatic bicarbonate doesn't get released to neutralize the chyme, then the bile doesn't get signaled to release either!

This can result in stored bile becoming stagnant and viscous, and in this way clogging up the liver. Usually here is where we would see gallstone formation.

If stomach acid is low, and the pancreatic bicarbonate doesn't get released to neutralize the chyme, then the bile doesn't get signaled to release either!

This can result in stored bile becoming stagnant and viscous, and in this way clogging up the liver. Usually here is where we would see gallstone formation.

Contrary to many conventional narratives, our bodies desperately need fat to maintain cellular structure, feel sated from our meals, build hormones, and to move waste out of the body, among many other purposes. Thus a lack of bile, and by extension, a lack of fat absorption can result in sugar cravings as we fail to feel satiated from meals, lowered or imbalanced hormone secretion as we deplete the raw material needed to make them, and constipation.

The combination of high pH in the stomach and the resulting low enzyme activity due to the lack of signaling cascades inevitably leads to large and dangerous particles of proteins and fats being left in tact as they enter the small intestine. This is consequence #6.

Consequence #6: Low acid + low enzyme activity = BIG and dangerous proteins and fats.

The villi and microvilli that line the porous and sensitive epithelial lining may become damaged as these particles are forced through the tube. Sort of like trees that get blown over in a storm.

Their truncation lowers the surface area where absorption can happen which significantly impacts the nutrients that we can assimilate. It also leads to the loosening of tight junctions and holes that form in the intestinal lining.

The damage caused by large protein and fat molecules can result in leaky gut. The compounds leak out into the blood stream, along with any other food stuffs moving through the passageway.

And we know what happens next!

The immune system doesn't recognize them, and so defaults to tagging them as invaders, which can incite a cytokine storm resulting in symptom onset.

To a certain extent, it doesn't matter if you're eating the most nutrient-dense food in the world, if it is undigested and leaks out of your gut it can still result in inflammation, or the development of a food sensitivity.

Finally, the leftovers make their way through the ilocecal valve and into the large intestines. But, if the undigested food particles are still present they may contribute to the ilocecal valve jamming open, allowing bacteria and waste matter to back up into the small intestine, which leads to consequence #7.

Consequence #7: Undigested foods, unneutralized pathogens, and volatile compounds create a toxic colon.

Once the waste passes into the lower bowel, it may be full of pathogens that weren't neutralized in the stomach, food particles that weren't digested in the stomach to feed them, and their volatile end-products. All of this can lead to a toxic colon that disrupts healthy flora and all of their conferred health benefits.

Consequence #7B: Low Butyric Acid levels = weakened cellular structure and more inflammation.

Low levels of beneficial microbes also likely means low levels of their end-products. Butyric acid is one of these end products, and typically serves as important fuel for the colonic cells. A lack of it can result in weakened cellular structure in the large intestine.

These structural impairments are correlated with the onset of digestive conditions such as IBS, Crohn's disease, Colitis, Celiac, and more.

It's hard to believe that all of that, the 7 digestive consequences in this video, derive directly from low stomach acid. But if you have a thorough understanding about how digestion actually works - which hopefully now, you do - it makes sense.

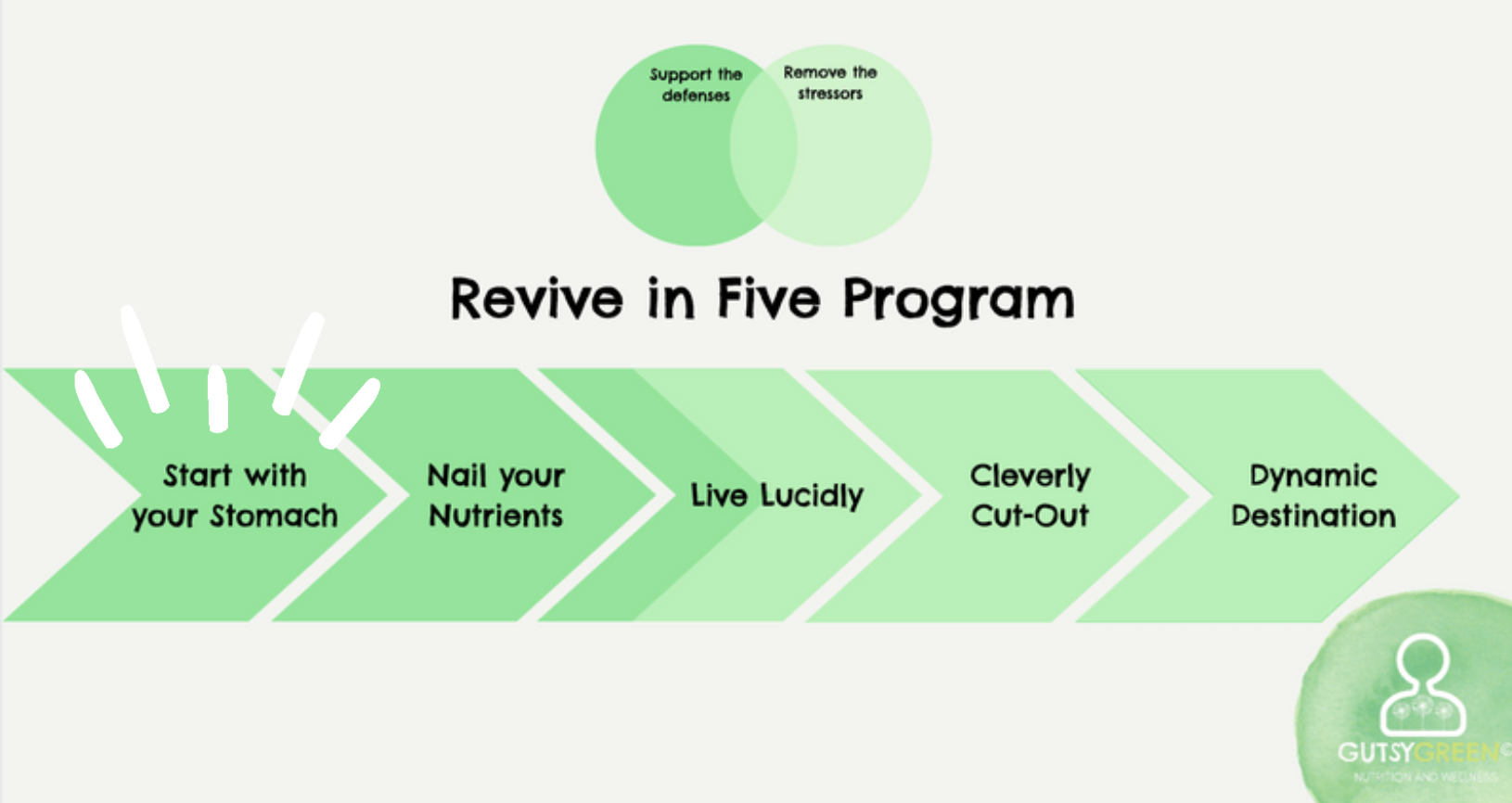

This is why the revive in five framework always starts here before we tackle anything else.

The good news is that our systems are robust and great at rebalancing themselves, but certain foundational pieces need to be in place. Strong HCl can be considered a root cause of intestinal and other digestive dysfunction, and, luckily, one that is among the easiest to fix.

We simply need to restore function, then fix the damage.

If you're interested in learning more about this, make sure to sign up for my free 7 day video challenge, where we'll talk about specific symptoms, conditions, and deficiencies that are especially well poised to be addressed by leveraging stomach acid, as well as what that process entails.

Thanks so much for joining me in this 3 part Digestive Dysfunction Deep Dive, and I'll look forward to catching you in the next one. Bye!